For many Las Vegans, Ralph Lamb was the ultimate lawman. He was the sheriff during the heyday of the mob and moved Las Vegas into the big leagues with law enforcement techniques, equipment and policies. His word was often the last word and he was well-liked and respected by the people who elected him. When dealing with guys like Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal, his word was the only one. He wasn't above reminding Lefty that unless a guest of Rosenthal's who was in the state's Black Book left immediately for McCarran Airport and caught the next flight out of town, Lamb would be back to deal with Rosenthal directly. Rosenthal complied.

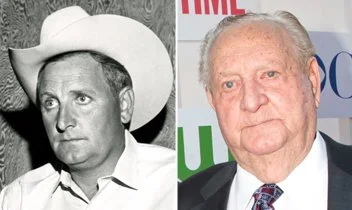

Ralph Lamb died Friday afternoon at the age of 88 after a brief illness and with his passing goes another chapter of Las Vegas history.

A.D. Hopkins wrote about Ralph Lamb for the book, The First 100 in 1999:

Ralph Lamb walked into the old airport on Las Vegas Boulevard and a man he had never before seen tried to kill him. "Shot at me three or four times and I wasn't as far as from here to that door," said the retired lawman, gesturing at a doorway perhaps 12 feet away. "And he didn't hit me once.

"I hit the concrete and shot at him a couple of times and I didn't hit him once. Then he was running away and I would have had to shoot him in the back, so I run him down, tackled him. He turned out to be just a wanted guy. He must have seen me coming in, maybe saw me fix my coat to cover my gun or my badge, and assumed I was coming for him."

Lamb never actually shot anybody in a lifetime of law enforcement, he said. People called him the cowboy sheriff, but gunplay wasn't his style. Fisticuffs were. Calf roping was. And politics were.

Lamb was sheriff for 18 years, longer than any Clark County sheriff. He forged a rural department into an effective urban one, and was largely responsible for merging the sheriff's office and the Las Vegas Police Department into the single police agency dubbed Metro.

"When I went to work there was hoods here, on the Strip, and the legitimate people mostly came later," said Lamb in a recent interview at his Las Vegas home.

"Everybody wants me to write a book but I never have said I would. The first guy to come to me on something like that was Sam Peckinpah. He said we could make a great movie and he'd get Clint Eastwood to make it. We were on our way, had it kind of in outline, when he died."

The opening scenes could have been in the Mormon farming community of Alamo, where most of the Lamb family worked on ranches. The sheriff's grandfather was killed working cattle, when a horse bucked him off.

Later, Lamb's father met much the same fate on July 4, 1938. His father was helping put on a rodeo at Tonopah. "He was trying to catch a runaway race horse," said Lamb. "There was a young boy on the horse. My dad rode up alongside and reached for the halter, and the runaway ran into his horse, hit right behind the saddle, and knocked it off balance. His own horse rolled right over him."

The deceased Lamb left 11 children, one so young that the father died with a telegram in his pocket announcing the boy's birth. The future sheriff was only 11. "My oldest brother, Floyd, had a ranch by then. He took in me and my sister Wanda," said Lamb.

Floyd would become a powerful state senator and the ranch would become the substantial Buckhorn, but both were still small in those Depression years. "There were mighty few jobs around, so a couple of my brothers and I cleaned the schoolhouse, dust-mopped, what have you. And my mother would preserve fruit, vegetables, beef, anything we could grow and put in a bottle. And that's how we got along."

Lamb served in World War II in the Pacific with Army intelligence. He aspired to become an FBI agent, but the family's immediate need for income put college out of the question even with the GI Bill. So he hired on as a Clark County deputy sheriff and soon became chief of detectives.

"It was pretty exciting work. You were out there on the Strip all the time, and mostly you dealt with guys coming here on the run. They had pulled a bank robbery, for instance, and they would come here, thinking it was an exciting place to spend their money, to kind of launder it. So we'd catch a lot of those guys.

"We knew people in all the hotels, the parking boys for instance, that we could ask, `Is there a stranger here?' "

He continued, "We were constantly trying to show the government we were in control of gaming. That was the purpose of the work card law." This law requires people employed in liquor and gaming operations to be fingerprinted and photographed, and to notify the sheriff's department if they move to another job.

Lamb departed the force in 1954 to form a detective agency with another ex-policeman. Their best-known client was Howard Hughes. "He was just a regular guy then; people made him a recluse because they wouldn't leave him alone. He was getting to be so famous.

"But he had everybody watching each other. Once I called him from a phone booth and he said, `Is there a guy in the phone booth next to you?' And there was. He had that guy watching me, and he was using me to check up and make sure that guy was doing it!"

Lamb ran for sheriff in 1958 against one-term incumbent Butch Leypoldt, and lost. But in 1961, when Leypoldt was named to the Nevada Gaming Control Board, the Clark County Commission appointed him to the unexpired term. He won election to a full term in 1962.

Lamb modernized the department. "At first, all anybody knew was that Bugsy Siegel built the Flamingo. Nobody knew who the young Turks were. So we started building an 86 file, working closely with the FBI. They would alert us that some hood was coming here, and usually we would surveil this guy awhile to see who he contacted, before we ever talked to him. So that way we built up intelligence information."

When the conversation finally took place, the hood would be informed that ex-felons had to register with the sheriff, told about the work card law, told that while the Mafia and Cleveland Syndicate operated casinos, they operated at the sufferance of Lamb and other elected officials and had better confine their activities to legal ones.

Lamb became friends with a police reporter, Don Digilio, who was later promoted to managing editor of the Review-Journal. Lamb was a country boy who had grown up on horses; Digilio was a polished urbanite who had barely seen one. But Lamb found it hard to talk to the media, so he would try out his announcements on Digilio, before making them public.

In a recent interview Digilio remembered a 1966 discussion with Lamb about Chicago mobster Johnny Rosselli. Rosselli became posthumously famous for helping the CIA in an unsuccessful assassination plot against Cuban premier Fidel Castro. But in December 1966 Rosselli, who had formerly visited Las Vegas without causing trouble, began making a regular circuit of Strip gambling clubs, for no apparent legitimate purpose. It looked to Lamb as if Rosselli were setting up a shakedown racket. Digilio recalled, "We said, there's always a shadow hanging over the place that nobody was going to touch any of these mob guys, maybe you ought to flex your muscles."

Digilio was a body-builder and former amateur wrestler who admired Lamb's willingness to get physical when necessary. But even he wasn't prepared for the enthusiasm with which Lamb did so on this occasion.

Rosselli and one Nicholas "Peanuts" Danolfo were sitting in a booth at the Desert Inn with Moe Dalitz, the proprietor, when Lamb sent in a rookie cop to tell Rosselli to come downtown and have that mandatory conversation with Lamb. Rosselli was 61 by then, but he had worked for Al Capone and had once beaten a narcotics rap when the arresting officer disappeared, permanently. He told the young cop to get lost, just as Lamb had expected. The sheriff had instructed the officer to be no hero that day, so the rookie retired to the parking lot, started his engine, and waited.

Now Lamb went into the resort and pointed out to Rosselli the discourtesy he had shown an officer. Then he grabbed Rosselli by his expensive necktie, dragged him across the table, and slapped him around a while. Danolfo started to jump in but Dalitz, spotting another officer coming up behind Danolfo to sucker punch him, grabbed his necktie and bade Danolfo resume his seat, observe and learn. Lamb threw Rosselli into the back-seat cage of the rookie's waiting cruiser and sent him to jail, ordering the extra touch of delousing. Rosselli made bail and left town. Ten years later, Rosselli's corpse was found floating in a 55-gallon oil drum off Miami.

One example was worth a thousand words, and Lamb had little further annoyance with mob misbehavior. It was even claimed, never in print but quite often, that if outlaws became too troublesome, Lamb's men would simply kill them.

To that assertion Lamb said recently, "I know of no policeman, in any department anywhere, who has ever participated in a murder such as you are describing."

Well, did it help to have the reputation?

"Yes," he replied.

Lamb's administration brought in a modern crime lab, a mobile crime lab, and the city's first SWAT team, which was kept secret until one of its snipers killed a bank robber who was threatening to shoot a hostage.

His most important contribution was helping form the Metropolitan Police Department. In the early 1970s, both the Las Vegas Police Department and the Clark County Sheriff's Department struggled with jurisdictional problems. People called the wrong agency to report crimes in progress, delaying police response. Both agencies were strapped for manpower, yet used a lot of it duplicating record-keeping and administrative functions.

Unlike most efforts at consolidation, the Metro legislation slid through the Nevada Legislature with ease, and Lamb ended up in charge of the joint agency. Most people attributed that to Lamb's political muscle -- by then his brother Floyd was an important senator and he could count on support from at least one county commissioner, his younger brother Darwin. But he gives much of the credit to the late John Moran, who was then Las Vegas chief of police, and would become his undersheriff.

"It wasn't hard because Moran and I were friends," said Lamb. And even policemen on the Las Vegas Police Department could see that it would be better if the agency were run by the sheriff, said Lamb. "The Las Vegas department had several good chiefs who couldn't keep the job," said Lamb. "They'd make somebody mad and they'd get replaced. So an elected head was better."

One of Lamb's efforts at efficiency, however, helped cost him the post that seemed made for him.

It was called the Task Force, and was an elite unit of experienced officers, handpicked by Lamb himself. If burglars became particularly aggressive, the Task Force set up sting operations buying stolen goods and then busting the sellers. Then it moved on to attack some other kind of crime. It made life miserable for pimps. When a hotel building boom brought in a new crop of hoods trying to gain a foothold in casinos, Task Force officers identified and kept track of them.

Lamb still thinks it worked like a charm. But many of his officers hated it. They regarded the Task Force as an arrogant outfit, hogging the glory and leaving the real work to everybody else.

Then there was Joe Blasko. A controversial Las Vegas officer known for beating up suspects -- one died -- Blasko ended up after the merger in Metro's organized crime unit. In 1978 he was accused of leaking information to mob boss Tony Spilotro, and Lamb fired him, but that sort of black eye does not quickly fade.

The longtime sheriff was also weakened by his indictment in 1977 for income tax evasion. The IRS attempted to prove Lamb spent more money than he earned as sheriff in such activities as building a home, complete with guest house and horsemanship facilities; proving it would mean Lamb had concealed income and evaded the taxes on it. And they attempted to prove that certain loans, including one for $30,000 from tough casino owner Benny Binion, were never meant to be repaid and were, therefore, taxable income.

However, U.S. District Judge Roger D. Foley acquitted Lamb of all charges. He said the IRS had failed to prove that anybody paid for the building materials, so they probably were gifts, not subject to taxation. "Many fringe benefits come to a public official which may be accepted along with the honest discharge of duty," said Foley. Similarly, said Foley, it was up to the government to prove that Binion's loan was never repaid, and it failed to do so. Lamb said recently he did pay Binion back.

But Lamb was politically wounded, and didn't recover. The following year he lost a bid for re-election, by a landslide, to his former vice squad commander, John McCarthy. "I wasn't paying attention to the campaign, because I was worrying about the trial," he said. And he admits that his past popularity may have made him overconfident.

"And I guess the public didn't think my department was too bad. Just one term later they elected my right hand man, John Moran, to replace the guy who replaced me." Lamb ran again in 1994, losing to Jerry Keller.

"A lot of guys it devastates to lose," said Lamb. "I never let it get that stage with me. When I lost an election I just went on and got a job, did something else."

More than 70 years old, Lamb rides every day, reads Louis L'Amour westerns, and remains too busy to wish he'd done anything different.

____________________________________

Ralph Lamb called them as he saw him and his legacy will not easily be forgotten. He was sheriff during a watershed era of Las Vegas history, helped modernize law enforcement in Las Vegas and his life story was almost made into a movie starring Russell Crowe and was to be directed by Clint Eastwood. The story did make it to television where Dennis Quaid played the legendary lawman for one season on Vegas.